The Origin of May Day

From time immemorial, people living through cold winters celebrated the coming of spring and the new planting-season, often with festivals on the 1st day of May. Similarly, the cessation of snow and frigid rain triggered the renewal of strikes, street protests, and struggles for justice and human rights.

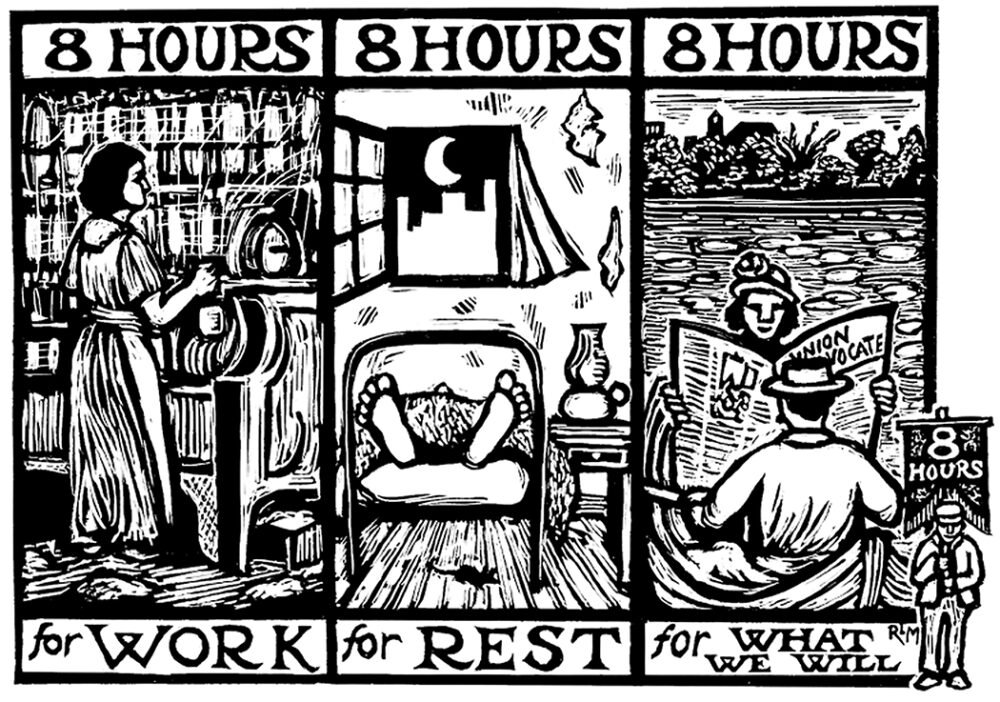

On May 1st, 1886, Chicago labor unions went on strike for an 8-hour work day with 80,000 people marching up Michigan Avenue in the first mass May Day March. They chanted: "8 hours for work, 8 hours for sleep, 8 hours for what we will."

Art by Ricardo Levins Morales.

Their strike was violently suppressed by the cops, a provocateur threw a bomb at a rally in Haymarket Square, and over the course of several days both strikers and police were killed and wounded. Many strikers were arrested on flimsy evidence and some were executed.

American unions then set May 1st, 1890 as a national day of action for the 8-hour day. Socialists in Europe did the same, declaring May Day to be International Workers Day. Since then, throughout the world May 1st has continued to be a day for social and economic justice movements of all kinds and issues.

In 1894, President Cleveland invoked the Insurrection Act and ordered the U.S. Army to violently suppress the Pullman Strike by railroad workers. This caused great public outrage. To appease public anger, Congress then declared the first Monday in September to be "Labor Day," a new national worker-related holiday, but one shorn from May Day's radical social-justice roots.