Why You Should Vote for Proposition 50

1. Introduction

President Trump recently asked the governor and state legislature of Texas to re-draw the map of the state’s 38 U.S. congressional districts. After the November 2024 elections 25 Republicans and 12 Democrats represented Texas in the House of Representatives. One seat, which represents a majority-Democratic district, remained vacant. So, we can assume that, before the elections, there were 25 Republican-majority and 13 Democratic-majority districts in Texas. The President asked the governor and state legislature of Texas to re-draw the map of the state’s congressional districts to increase the number of Republican-majority districts by 5. This would increase the total number of Republican-majority districts in Texas to 30 and decrease the number of Democratic-majority districts to 7.

To do as the President asked, in August 2025 the Texas state legislature re-drew that map of Texas congressional districts, which the governor then approved. Because representatives in Congress serve two-year terms, the new map did not immediately change the partisan composition of the Texas delegation. In 2027, however, a new delegation will take office in Washington, and that delegation is likely to consist of 30 Republicans and 8 Democrats—assuming that a Democrat will hold the currently unfilled seat.

In the U.S. House of Representatives, there are 220 Republicans, 212 Democrats and 3 unfilled seats. If no other state re-draws the map of its congressional districts, it is likely that in 2027 the U.S. House of Representatives will include 225 Republicans and 207 Democrats. This would, indeed, change the politics of the House: Republicans would be able to lose as many as 8 votes on any issue and still have a majority—which would make it easier for the President and Republicans in Congress to realize their agenda, and more difficult for Democrats to resist it.

Since the Texas redistricting, at least six states have joined in this effort to destroy democracy. Florida, Indiana, Kansas, Missouri, North Carolina, and Utah have announced that they, too, will re-draw the maps of their congressional districts to increase the Republican majority in the House and weaken Democrats’ position in Congress still further.

2. How Congressional Districts are Created.

The map of U.S. congressional districts is created in two steps. The first step determines how many districts each state will have. The second step determines the locations and borders of districts in each state.

Step 1. Determining the Number of Congressional Districts in Each State

The following passage from Article I, Section 2 of the U.S. Constitution sets rules for determining the number of congressional districts that each state will have—and, therefore, how many representatives each state will send to the House of Representatives.

Representatives…shall be apportioned among the several States which may be included within this Union, according to their respective Numbers… The actual Enumeration shall be made within three Years after the first Meeting of the Congress of the United States, and within every subsequent Term of ten Years, in such Manner as they shall by Law direct… each State shall have at least one Representative.

This passage requires, first, that representatives are “apportioned among the several states…according to their respective Numbers.” This means that the number of individuals living in a state determines the number of representatives that the state has in Congress.

Because each state’s population determines its representation in Congress, we need accurate counts of these populations. Because populations change over time, Article 1, Section 2 requires that state populations be re-counted, and the number of congressional districts in each state re-calculated, every ten years. Hence, the decennial census of the U.S. Population that the federal Department of Commerce conducts every decade.

The Method of Equal Proportions

Article I, Section 2 requires that the number of congressional districts in a state and, therefore, the number of representatives that it has in Congress, shall be determined by the state’s population—i.e., the number of individuals living in a state. How is the number of districts and, therefore, the number of representatives determined by, or derived from, the number of individuals in the population?

Since 1941, Congress has derived the number of congressional districts in a state from the number of individuals in the state using The Method of Equal Proportions. To each state, this method assigns a number of districts such that: the population per district in that state is equal to the population per district in every other state—or as nearly equal as possible. Because the number of representatives equals the number of districts, the Method of Equal Proportions assigns a number of representatives to a state such: the population per representative in that state is equal, or as nearly equal as possible, to the population per representative in any other state.

The population per representative in a state is the population of the state divided by the number of congressional districts in the state. Because each state has one representative for each of its districts, the population per representative in a state is also equal to the population of the state divided by the number of representatives in the state’s congressional delegation. So, for any state, S,

Fifty states are represented in Congress. We could make a list that included all of the states: S1, S2, … S50. If this list were alphabetical, S1 would be Alabama (AL), S2 would be Alaska (AK), and so on until we reach S50, which would be Wyoming (WY). We can use the equation just above, to express the population per representative for each state:

⋮

From the census, we know the population of each state. It remains to assign to each state a number of congressional districts—and, therefore, a number of representatives. The Method of Equal Proportions does this by assigning to each state the number of congressional districts that makes the population per representative for all states equal to one another—or as nearly equal as mathematically possible. The objective of The Method of Equal Proportions is to assign a number of districts to each state such that every member of Congress represents the same number of individuals. An assignment that meets this condition ensures that the voice and vote of each member will have the same weight and authority with respect to decisions affecting the nation.

3. Determining District Locations and Boundaries

Once Congress has assigned a number of districts to each state, it remains for states to determine the locations and borders of each district. In most cases, state legislatures specify district locations and borders in legislation subject to approval by their governors. There are, however, exceptions to this practice. Arizona, California, and Michigan, for example, have independent or bipartisan commissions that draw maps of state legislative districts. These maps are not subject to approval by a state legislature or governor.¹

Federal Law

Regardless of their authors, district maps must comply with federal law, which includes the following restrictions.

Equal Population: Article 1, Section 2 of the U.S. Constitution requires that congressional districts must have equal or nearly equal populations (Wesbury v. Saunders (1964)). The Method of Equal Proportions applied to the decennial census should ensure that the population of any district in any state will be equal, or nearly equal, to the population of any district in any other district in any state.

Protection Against Racial Discrimination: The 14th and 15th amendments of the U.S. Constitution, along with the Voting Rights Act of 1965 make it illegal for states to draw congressional districts in a way that denies racial or language minorities the right to vote, or that diminishes the influence of their votes. Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act, for example, requires that racial and language minorities have the same opportunity as other citizens to “participate in the political process and to elect representatives of their choice.”

Historically, courts have read the Voting Right Act as prohibiting states from splitting minority populations into separate districts, for example, in a way that prevents minority candidates from winning seats in Congress. The courts have also interpreted the Voting Rights Act as prohibiting states from “packing” a minority population into a single district for the purpose of limiting the number of seats held by representatives of such populations. More generally, in Shaw v. Reno (2013) and Miller v. Johnson (1995), the Supreme Court has ruled that race may not be the predominant factor that determined how a state drew its congressional maps.

Contiguity: Federal custom and case law require that all congressional districts must be contiguous. A district is continuous just in case, it is possible to travel from any one point in a district to any other point in the district without leaving the district. This restriction prevents states from assembling a congressional district out of two or more physically disconnected regions.

Respect for Minority Representation: As we observed above, the Voting Rights Act requires that state maps of congressional districts must not split minority communities into separate districts in a way that prevents such communities from electing a representative from either district. The Voting Rights Act also prohibits “packing” minority communities into one or a very few districts, once again, in a way that will limit their representation in Congress.

4. Gerrymandering

Federal law prohibits states from drawing congressional districts in a way that deprives racial and language minorities of the same opportunity as other citizens to “participate in the political process and to elect representatives of their choice.” States are specifically prohibited from drawing maps in a way that divides racial or language communities geographically in a way that inhibits their ability to elect representation in Congress. Neither are states allowed to concentrate racial or language groups into districts for the purpose of limiting the number representatives that they can elect to Congress.

There is, however, little or nothing in federal law that prohibits states from drawing districts in ways that favor one party over another. Little or nothing prevents states from drawing congressional districts in ways that make the President and candidates who support him more likely to win future congressional elections in the state.

The President did not ask Texas to re-draw its congressional districts to make it unlikely that that the state would elect Black or Latino candidates to Congress: He asked the governor and state legislature of Texas to re-draw the map of its congressional districts specifically to create at least five more Republican-majority districts and eliminate at least five Democratic-majority voting districts. An effect of this might be to dimmish minority representation, but its announced objective was not that.

To draw district maps explicitly for the purpose of creating or destroying partisan advantage is to engage in one form of gerrymandering—i.e., partisan gerrymandering. Gerrymandering for partisan purposes—e.g., drawing congressional districts to make it more likely that more districts will favor one party over another—is not a federal crime. In Rucho v. Common Cause (2019), the Supreme Court ruled that federal courts may not strike down state district maps for partisan gerrymandering alone—though many states have made partisan gerrymandering a violation of state law.

Partisan gerrymandering may be unconstitutional, if it entails racial gerrymandering—i.e., drawing district maps that have the effect of preventing racial or language minorities from gaining and keeping representation in Congress. The U.S. Supreme Court ruled that racial gerrymandering violates the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment if race is the predominant factor in drawing district lines and the plan lacks sufficient other justification (Shaw v. Reno 509 U.S. 630 1993). The Court has also ruled that some cases of partisan redistricting in a state do, indeed, constitute racial gerrymandering.³ The lesson here is that what at first appears to be merely partisan gerrymandering—and, therefore, legal—may also be a case of racial gerrymandering—and, therefore, not legal.

The President, however, has not asked the states to engage in racial gerrymandering. He has asked them to engage in political gerrymandering, to ensure that Republicans control Congress after the 2026 elections. One way to ensure this is to re-draw congressional maps to increase the number of Republican-majority districts.

Partisan Gerrymandering is Unjust

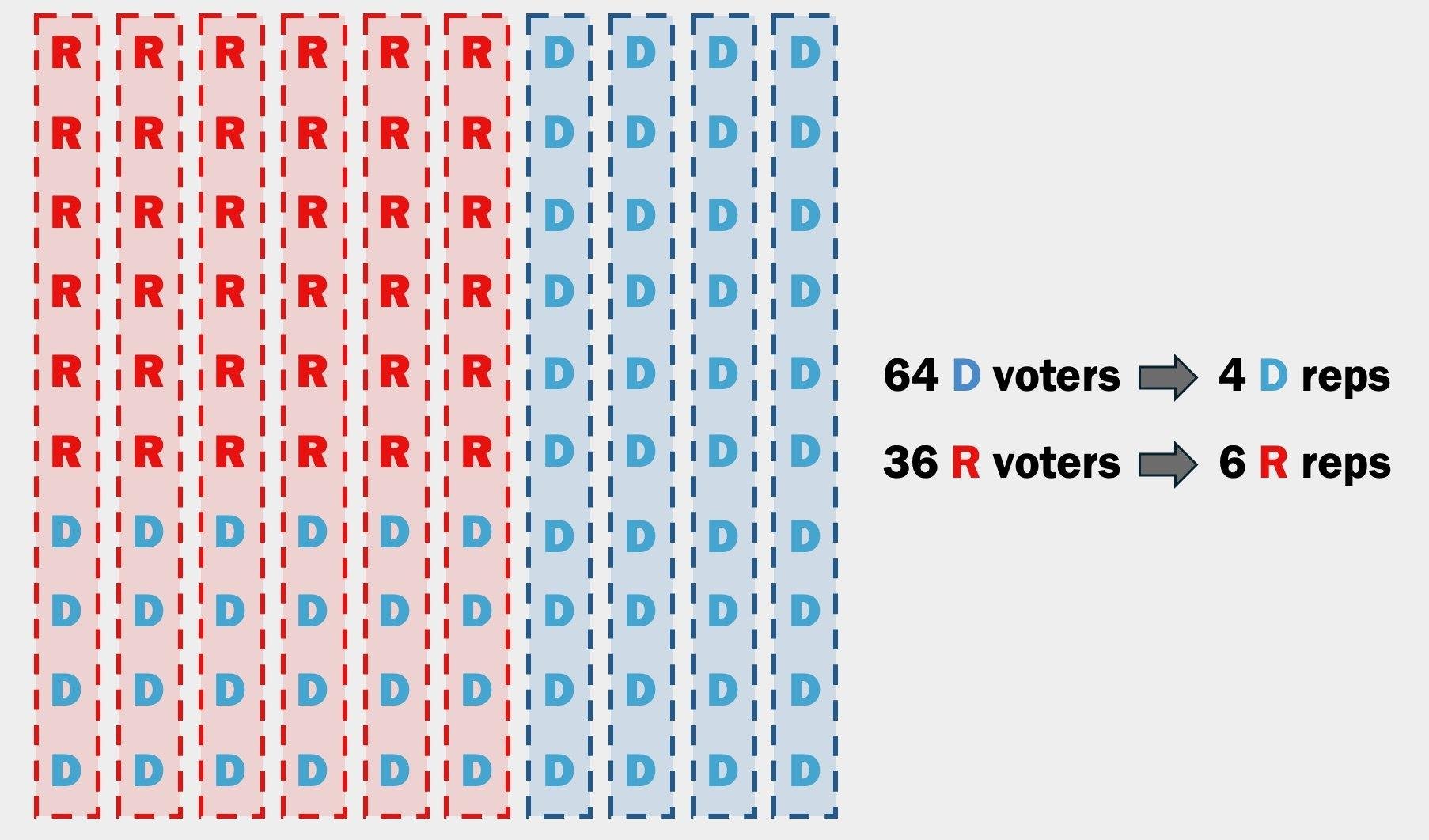

While partisan gerrymandering is not a federal crime, it is hostile to fair and equal representation in Congress and, therefore, hostile to justice itself. To see this, consider the (fictional) case of a state that has a population of 100 citizens equally partitioned into 10 congressional districts. If these districts satisfy the requirement of equal population per district within the state, then each of the ten districts will have 10 citizens. Suppose as well that the state population consists of 64 individuals who vote for Democratic candidates, and 36 who vote for Republican candidates. In that case, the state as a whole qualifies as a strongly Democratic-majority state. So, if the state’s congressional delegation were consistent with the partisan composition of the state, we would expect the state to send 6 Democratic and 4 Republican representatives to Congress.

But suppose that the State has been gerrymandered as depicted in Diagram 1 below. Each column in the diagram represents a district consisting of 10 voters.

Reading from left to right, the first six districts in the state have 6 Republican Party voters and 4 Democratic Party voters. The remaining 4 districts have 10 Democratic Party voters each.

Diagram 1: A Partisan (Republican) Gerrymander

Assume that the partisan composition of a district determines who will represent the district in Congress. The first six districts have six Republican and four Democratic Party voters—so, we assume that these six districts would each send a Republican representative to Congress. In the remaining 4 districts all voters support Democratic Party candidates—so we assume that these districts will send representatives from the Democratic Party to Congress. The congressional delegation of the state, then, will consist of six Republican and four Democratic Party representatives—not the six Democrats and four Republicans that we might have expected.

In this scenario, a large majority of citizens in the state would have voted for congressional candidates from the Democratic Party, but partisan gerrymandering concentrated Republicans into six of the ten districts, which led to a large Republican majority in the state’s congressional delegation. It is an ideal of democracy that, other things equal, policy will be consistent with the will of a majority of voters. Here, we see that gerrymandering is hostile to that ideal.

This fact about partisan gerrymandering has other consequences:

Partisan gerrymandering undermines the ideal of “one citizen, one vote.” Partisan gerrymandering causes the votes of some voters, in effect, to count for more than the votes of others. In the preceding example, fewer citizens vote for Republican Party policies than for Democratic Party policies—and, yet the Republicans win. In this sense, gerrymandering undermines political equality among voters, by undermining the idea that every citizen’s vote has the same weight in deciding what the government does.

Partisan gerrymandering is hostile to accountability. In our example, partisan gerrymandering leads a minority to gain power over a majority. For the same reason, gerrymandering will allow a minority to retain power, by making it hard or impossible for a majority to vote minority officeholders out.

Partisan gerrymandering discourages voters’ participation. Because partisan gerrymandering undermines political equality and political accountability, it is likely to discourage participation in voting. Participation in voting is the breath of democracy. Because partisan gerrymandering discourages people from voting, it is an enemy of government by the governed.

Trump’s request that Texas and other red states gerrymander their electorates, therefore, is not merely an act of political self-interest: It is an attack on fundamental ideals of democracy.

Why Should We Vote for Proposition 50?

It is unheard of for a President to call for a mid-decade redistricting. If we allow it to proceed only in the Republican states, the 2026 election will have one set of rules for the Democrats, and another for the Republicans. People often accuse Democrats of bringing a knife to a gun fight—in this mid-decade redistricting, Trump is attempting to disarm Democrats.

Proposition 50 would allow California to help level the political playing field. Its objective is to counteract and discourage partisan gerrymandering by other states and to cause the President and other Republicans to retreat from their present course of action.

Unlike the redistricting in the Republican states, redistricting under Proposition 50 would be temporary: Maps drawn under the authority of Proposition 50 would expire automatically in 2030, when the next decennial census would take place. Moreover, in 2030 California’s independent, non-partisan re-districting commission would re-draw districts in the state free of partisan gerrymandering. A vote for Proposition 50, therefore, is a vote to counteract partisan re-districting by other states at the (unprecedented) request of the President—and return the nation to the ideals of fair, representative government; political equality; and justice.

Footnotes

¹ The Method of Equal Proportions more or less guarantees that this will be the case.

² In 1812, Governor Elbridge Gerry, a member of the Democratic-Republican Party, signed into law a redistricting plan designed to favor his party in state elections. One district near Boston was drawn in such a bizarre, twisting shape that critics said it resembled a salamander. A political cartoon published in the Boston Gazette that same year depicted the district as a monster with claws, wings, and a long tail—and labeled it the “Gerry-mander.”

³ For example, on October 6th, 2026, Democracy Docket reported that the August 2025 redistricting in Texas, in fact aimed to eliminate at least some majority-minority districts, thus violating the Equal Protection Clause. The Plan is now under scrutiny by a federal court in El Paso.