Deep dive on Proposition B (February 2024)

This follows our Deep Dive from 2020 on the SFPD staffing minimum that existed from 1994 to 2020.

There will be a new proposition on the ballot in February–March 2024, Proposition B, which proposes to put in a new staffing minimum. We’ve written this new Deep Dive to explain what Prop B would and would not do.

Executive summary

Since 2020, the City has followed a process created by that year’s Proposition E for the Chief and the Police Commission to advise the Board of Supervisors on what they think police staffing levels should be.

The Board of Supervisors sets the budget for all City departments, including the San Francisco Police Department. If the Board wants to add budgeted staff positions to the SFPD, they have the power to do so, subject to the constraints of the budget.

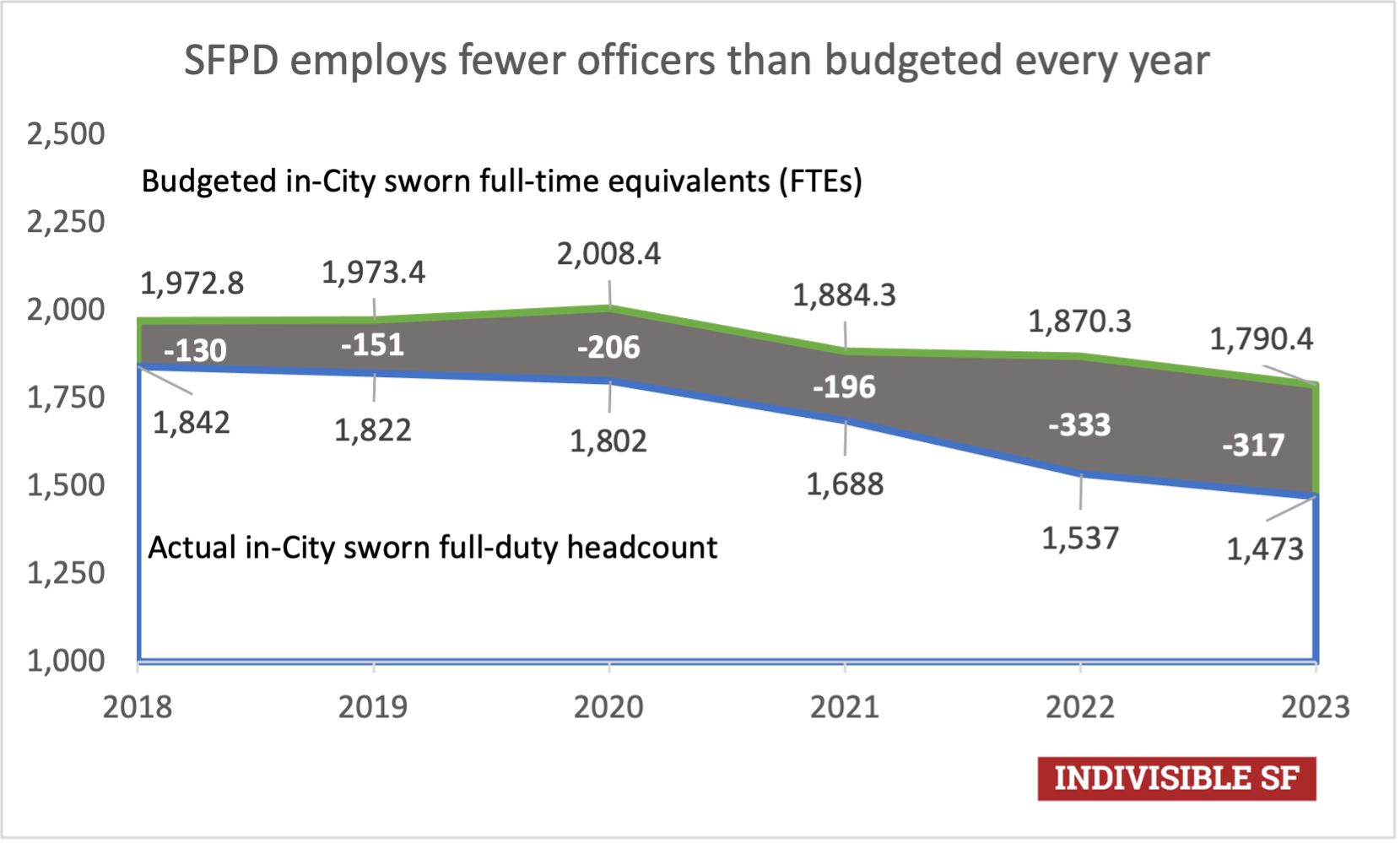

However, even if they add budgeted positions, that does not equate to hiring actual officers; the City has long budgeted for more officers than it actually employs. Attracting new hires is where the City has struggled to increase staffing.

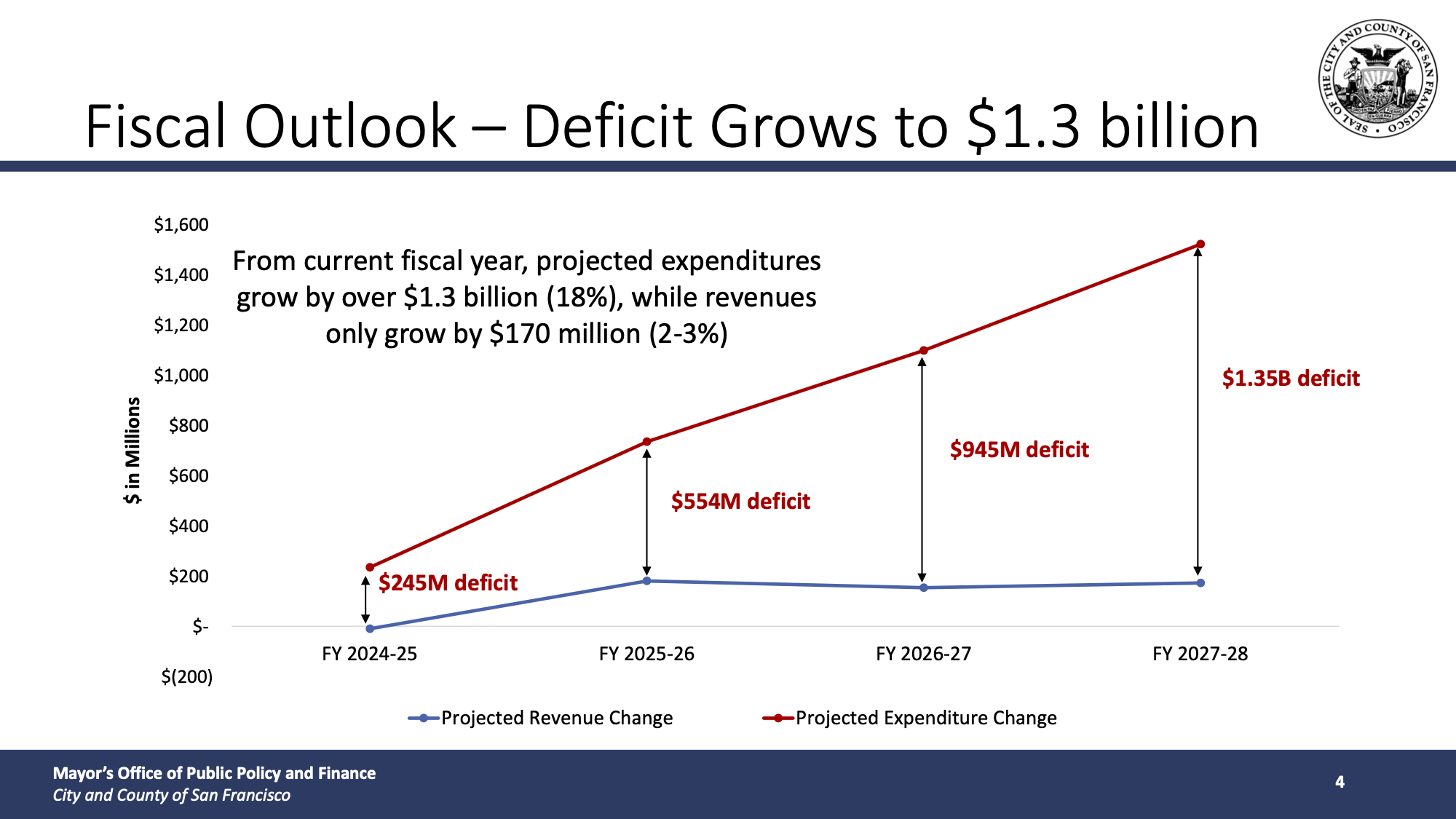

Moreover, successful hiring would increase the police’s already heavy drain on the City’s increasingly limited budget. The Mayor’s office projects rapidly deepening deficits for at least the next four years.

There’s a new measure, Proposition B, on the February–March 2024 ballot that promises to hire more cops if enough revenue can be raised to do so. This Deep Dive will dig into the details, but here’s an overview:

Prop B does not hire more cops. The main obstacle to hiring more cops is having the money to attract them. If the money were there, the City could hire more cops today. But the money isn’t there. Prop B does not fix this.

Prop B would not kick in until an entirely hypothetical future event. Namely, a tax measure that would generate enough revenue to meet Prop B’s targets. No such measure is on the February ballot, and as far as we’re aware, none is planned.

Prop B would not increase the police budget for some unknown number of years. Our current budgeted strength is already above Prop B’s initial minimum. Only after Prop B kicks in (someday) would it impose a minimum higher than today’s budgeted level.

Prop B would divert money to attracting new officers, and give it to the SFPD to spend. When Prop B kicks in, it will create a fund and require the Board to appropriate millions of dollars to fill it over five years. The money can only be used by the SFPD, and is meant to be spent toward attracting and hiring new officers.

In the meantime, we’re more likely to see cuts than increases. The Mayor has already asked for a freeze on police hiring and the closure of existing vacancies, because we just don’t have the money.

What’s the status quo as of January 2024?

Currently, the Board of Supervisors controls police staffing through the power of the purse, under advisement from the Chief of Police and the Police Commission.

Every couple of years, the Chief of Police sends the Police Commission a report documenting how many full-duty sworn officers the SFPD currently has and telling the Commission how many he thinks the Department needs. Later that same year, the Police Commission holds a hearing on that report.

In the annual budget process, the Board of Supervisors decides how to reconcile the recommendations of the Chief and the Police Commission, the Mayor’s budget instructions, the Board’s own priorities, and the amount of money the City is expected to have in the coming fiscal year. The Board passes ordinances to appropriate money to City departments, including the Police Department.

So the Board of Supervisors, today, can add or remove budgeted positions from the Police Department (as with all City departments) as they see fit. The only real limit on this is how much money the City has available to spend—and the Mayor’s office is forecasting rapidly growing deficits over the next several years.

Source: Mayor’s budget instructions deck, 2024.

We’re so skint that Mayor Breed has explicitly asked for no new police hiring. No new vacancies, and existing vacancies will be closed to save money.

Source: SFPD budget presentation to Police Commission. 2024.

How many officers does the SFPD have now?

The SFPD, in its budget presentation to the Police Commission on January 17, counted 1,725 sworn officers as of December 2023, of whom 1,473 are full duty sworn officers. The same presentation puts the budgeted number of full-time equivalent (FTE) in-City full-duty sworn positions for 2023 at 1,790.4, with an increase to 1,834.8 this year and a slight decrease to 1,834.6 next year.

(The total number of budgeted sworn FTEs is going up both this year and next, but the 2025 increase goes entirely to airport officers. And every year, the non-airport side of the police budget includes 200 FTEs for officers not on full duty.)

The gap between the number of budgeted sworn officers and the number of people walking around with badges has been growing for some time, as shown in the chart below.

The proposition’s Findings section explains why the City has had so much difficulty closing that gap: there are fewer prospective officers, police departments everywhere are competing for them, and neighboring jurisdictions have been offering generous hiring bonuses to sweeten the pot. The proposition cites the example of Alameda, which offered $75,000 bonuses.

We haven’t been doing that because we can’t afford to.

Does the City have to have a certain number of police officers?

Not anymore. We used to, from 1994 to 2020. That Charter-mandated minimum and the problems it caused were documented by our 2020 Deep Dive.

Since Proposition E passed in 2020, the Charter does not specify a minimum number. The Chief of Police, the Police Commission, the Mayor, and the Board of Supervisors are responsible for determining how many police we should have.

What are sworn officers and civilian personnel?

An employee of the police department can be either a civilian employee or a sworn officer. Sworn officers are those we typically think of as “police officers” or “peace officers,” and are more expensive than civilian staff.

Civilianizing a position means reassigning work to a civilian employee. It can mean either shrinking the sworn force (transferring duties to civilians and closing out those sworn positions) or growing the civilian force (hiring new civilians) while maintaining the sworn force.

The Charter requires that “No sworn officer shall be laid off in order to convert a position to civilian personnel,” so the City can’t move work to the civilian force by firing sworn officers—it can only be done as opportunities arise through sworn-officer attrition.

What does “full duty” mean?

Full duty is the opposite of “modified duty,” also known as “light duty.” That’s defined by Department General Order 11.12, “Temporary Modified Duty/Reasonable Accommodation.”

If the Charter were to require a certain minimum number of full duty sworn officers, the department would generally be required to employ more sworn officers than the minimum. Otherwise, if an officer is injured and needs to go on modified duty, retires, or dies, that could bring the department below the mandatory minimum number of full-duty officers, in violation of the Charter.

What would the proposed Charter amendment do?

Well, at first, Prop B would do exactly nothing, for an indeterminate amount of time. It only kicks in after another, currently entirely hypothetical, measure passes.

And, of course, Prop B wouldn’t do anything to address causes of crime, such as organized crime rings or poverty. The former is a problem that should be worked on by the police we currently have; the latter is not a police matter at all.

But the question is what Prop B would do, so let’s dig into that.

First off, as we said above, nothing would happen until the passage of some hypothetical future tax measure. That measure is not on the February ballot and no text has yet been proposed for it, as far as we know.

We should also note that nothing in this proposed amendment restricts that provision to trigger on tax measures specifically for police staffing. The tax measure that sets Prop B off might be intended to pay for something else, like schools or housing, and then get captured if it raises enough money to trigger this proposed language. We’re not attorneys, so we can’t say whether a tax measure worded carefully enough to evade this provision (e.g., by creating a fund, restricting the purposes of its expenditures, and directing the new revenues to it) would work.

Once the entirely hypothetical tax measure passes and the City Controller certifies that it’s generating enough revenue, only then does the new staffing minimum begin—and it’s a doozy of a process:

The City would start on a fixed five-year timeline, required to budget for no fewer than 1,700 Full-Duty Sworn Officers the first year, then 1,800 the following year, then 1,900, then 2,000, and then 2,074 in the fifth year. (Don’t ask us how they came up with that number.) For each of those years, the Mayor and the Board would be absolutely required to budget for no fewer than this many Full-Duty Sworn Officers. Lean times? Recession? Too bad; Charter says that money goes to the police.

The Mayor and the Board are currently budgeting for 1,834.8 sworn FTEs in fiscal year 2024. After five years, Prop B would require the City to have added more than 200 more officers’ wages to the police budget than we have budgeted today.

If the Board’s appropriation proves insufficient, Prop B would empower the Police Department to introduce an ordinance to give them even more money.

Along that same five-year period, Prop B would establish a “Police Full Staffing Fund,” starting with a mandatory $16.8 million appropriation in the first year, and further mandatory appropriations each year after of $75,000 times however many officers short the City is that year (limited to $30 million per year), until the five-year period is over.

The Police Full Staffing Fund would be available both for compensating existing officers and use in recruitment efforts (e.g., hiring bonuses). It’s entirely up to the SFPD to decide how they spend the money, though Prop B says it’s to be used “exclusively to support full staffing of Full-Duty Sworn Officers.”

Any money the Department doesn’t spend from the Fund would be returned to the City’s General Fund at the end of the fiscal year, though if the five years aren’t up yet, some or all of it would be immediately re-appropriated back to the Police Full Staffing Fund.

The Fund would expire after ten years (five years after the last year of the minimum).

If spent effectively, the Police Full Staffing Fund is the part of this measure most likely to actually increase police staffing.

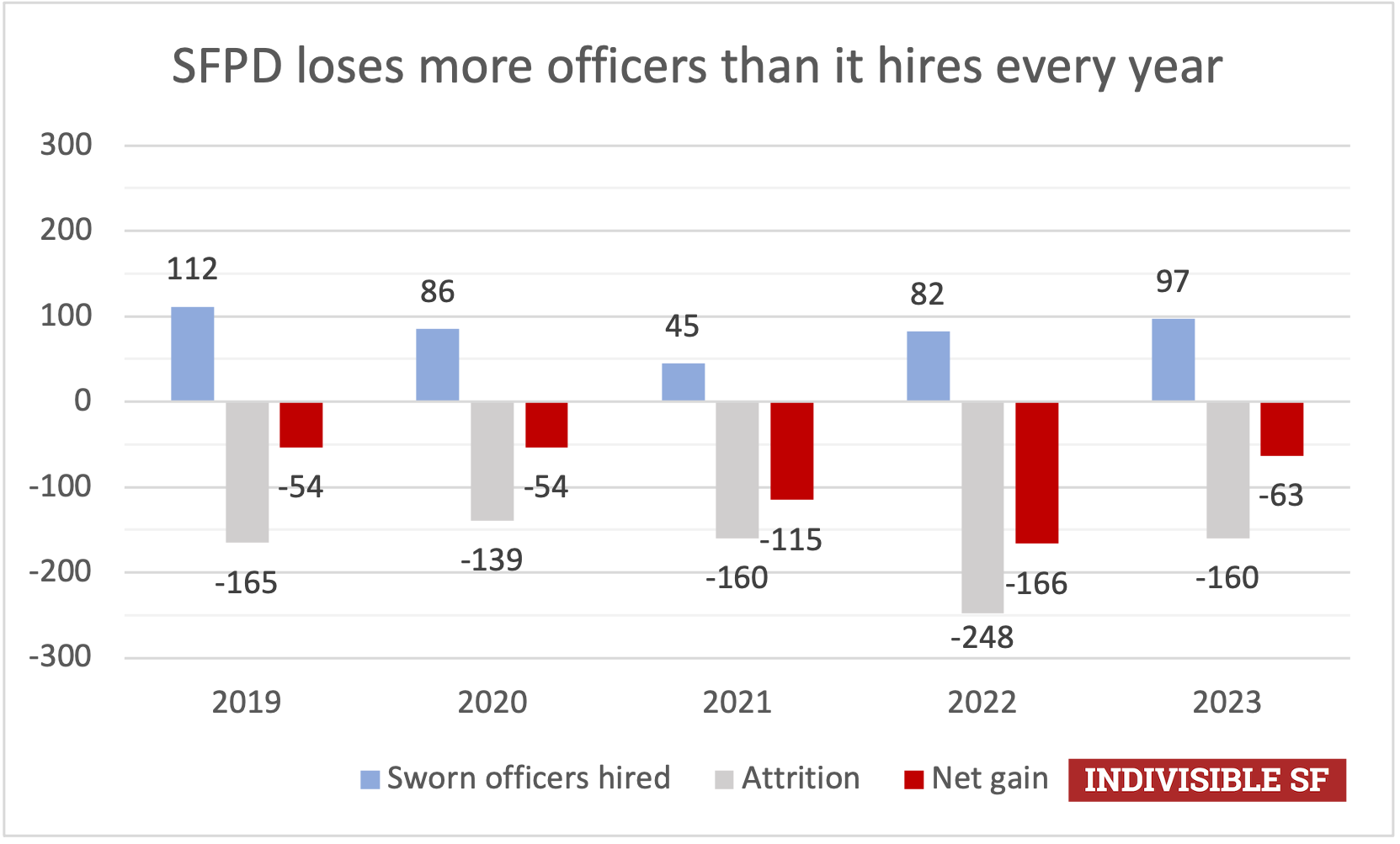

To increase the real headcount by 100 officers every year, the City would need to hire 100 net new officers every year.

Source: Data from SFPD budget presentation to police commission, 2024

The City currently hires approximately 100 officers per year before attrition, but ultimately loses between 50 and 200 officers per year to attrition, so the City would need to hire as many as 300 officers per year to meet Prop B’s targets.

Prop B, in a nutshell, says that once we can afford to do that, we’ll have to.

So: for five years after some as-yet-unseen tax measure passes, the City government would be locked into a process of escalating Charter-mandated police staffing minimums and spending money from a Police Full Staffing Fund (funded by the revenues from that tax measure, whether it was intended for that or not) toward police recruitment efforts.

After that period ends, we’d go back to a modified version of the current advisory process, except the advisory cycles would be every five years instead of every two.

The Controller’s summary of Prop B notes that

This proposed amendment is not in compliance with a non-binding, voter-adopted city policy regarding set-asides. The policy seeks to limit set-asides which reduce General Fund dollars that could otherwise be allocated by the Mayor and the Board of Supervisors in the annual budget process.

How would a new mandatory staffing minimum affect San Francisco?

Currently, the Board of Supervisors decides how to divide the police budget between sworn officers and civilian personnel, taking into account the proportion of Department work that can be done by civilians as opposed to that which must be done by sworn officers.

When we had a staffing minimum in the Charter from 1994 to 2020, it inflated the number of sworn officers above what was actually needed. The City spent money on extra sworn officers that it could have spent on civilian employees to do the same work at lower cost, which the March 1998 Phase II report called “reverse civilianization.”

Currently, the ultimate responsibility for deciding how much money to spend on police staffing lay with the Board. Prop B, if and when it kicked in, would take that out of their hands, and compel the City to hire up toward its arbitrary targets.

We should note that because Prop B is contingent on a future tax measure, the proposed mechanism won’t spend money we don’t have. It won’t impose its arbitrary minimums until we have the money to meet them.

However, it could divert money that was supposed to be for something else until the five years is up. It could also discourage the passage of new tax measures since the money might get diverted if the new tax revenue sets off Prop B—which seems poorly timed as we head into a series of budget deficits.

There’s also the broader issue of policing as substitute for social programs that prevent crime and promote public safety. We’ve divested from housing, education, healthcare including mental healthcare, and addiction treatment, and shoveled the money into policing. Then, when people are unhoused, can’t get a job, and are suffering, we criminalize them.

Currently, we can choose to break out of this cycle; Prop B, if and when it goes off, would lock us in for its five-year period.

Appendix: What’s the current Charter text on police staffing?

The process as of January 2024 is set by a provision in the San Francisco City Charter, under Section 4.127, the section that creates the San Francisco Police Department:

POLICE STAFFING. By no earlier than October 1 and no later than November 1 in every odd-numbered calendar year, the Chief of Police shall transmit to the Police Commission a report describing the department’s current number of full-duty sworn officers and recommending staffing levels of full-duty sworn officers in the subsequent two fiscal years. The report shall include an assessment of the Police Department’s overall staffing, the workload handled by the department’s employees, the department’s public service objectives, the department’s legal duties, and other information the Chief of Police deems relevant to determining proper staffing levels of full-duty sworn officers. The report shall evaluate and make recommendations regarding staffing levels at all district stations and in all types of jobs and services performed by full-duty sworn officers.

By no later than July 1 in every odd-numbered calendar year, the Police Commission shall adopt a policy prescribing the methodologies that the Chief of Police may use in evaluating staffing levels, which may include consideration of factors such as workload metrics, the Department’s targets for levels of service, ratios between supervisory and non-supervisory positions in the Department, whether particular services require a fixed number of hours, and other factors the Commission determines are best practices or otherwise relevant. The Chief of Police may, but is not required by this Section 4.127 to, submit staffing reports regarding full-duty sworn officers to the Police Commission in even-numbered years.

The Police Commission shall hold a public hearing regarding the Chief of Police’s staffing report by December 31 in every odd-numbered calendar year. The Police Commission shall consider the most recent report in its consideration and approval of the Police Department’s proposed budget every fiscal year, but the Commission shall not be required to accept or adopt any of the recommendations in the report.

The Board of Supervisors is empowered to adopt ordinances necessary to effectuate the purpose of this section regarding staffing levels including but not limited to ordinances regulating the scheduling of police training classes.

Further, the Police Commission shall initiate an annual review to civilianize as many positions as possible and submit that report to the Board of Supervisors annually for review and approval.

(We inserted a paragraph break into the above for clarity; it should not be used as a legal citation. See the above link for the current legal text.)

The Charter also contains a section, 16.123, on “civilian positions within the Police Department:”

(a) Positions in the Police Department may only be converted from sworn to civilian as they become vacant. No sworn officer shall be laid off in order to convert a position to civilian personnel.

(b) If the Mayor or any member of the Board of Supervisors proposes to convert positions in the Police Department from sworn officers to civilian personnel through the budget process, the Controller and the Chief of Police shall report on whether the reduction would decrease the number of police officers dedicated to neighborhood community policing, patrol, and investigations or would substantially interfere with the delivery of City public safety services, including services to protect the public in the event of an emergency. In preparing the report required by this subsection (b), the Chief of Police shall solicit input from the Police Commission.

References

Budget documents for FY2024–2025 (particularly the Mayor’s budget instructions)

January 17, 2024 Police Commission meeting (with SFPD budget presentation)

Some older resources that are still relevant: